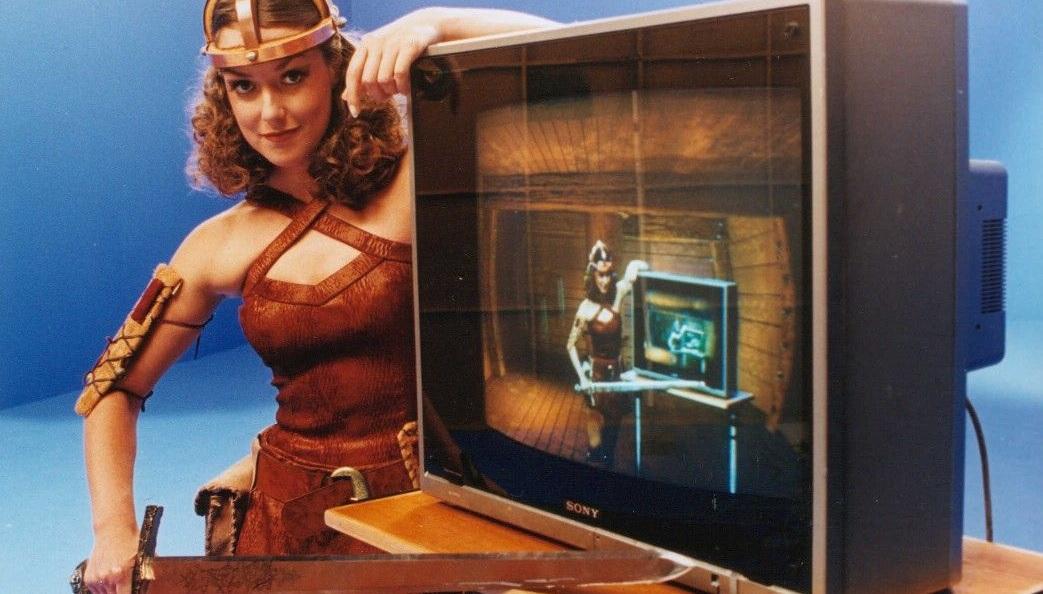

Knightmare was made using bluescreen (or chromakey) technology. This is more familiar to us now, but it was technically demanding in the mid-1980s.

How did chromakey work in Knightmare?

Knightmare used two identical blue sets (known as 'voids'), which were both evenly lit.

Behind the scenes, technicians used computers to replace the blue with different backgrounds and add atmospheric lighting and effects.

The original dungeon rooms were painted by artist David Rowe. These needed to match the exact dimensions of the blue void.

The Travelling Matte Company then used a Spaceward Supernova computer to apply these backdrops and add the finishing touches.

The superimposed graphics created an authentic dungeon environment for games players.

In later years, photography and stills of real-life locations were digitally enhanced and mapped against the void. This allowed the producers to broaden the scope of the fantasy kingdom.

Coping with shadows

Even with uniform lighting, a roaming dungeoneer was always going to create shadows. To compensate for this, Knightmare used a luminescence-sensitive chromakey system.

This system would offset any variations in lighting by adjusting the brightness of the graphics. Shadows from the players caused subtle changes to the background effects.

'Spacehog', previously of Anglia TV and Televirtual (including pre-production crew for Knightmare), told us:

"The room was consistently lit; any variations in brightness of the walls was transferred to the graphics.

"But this didn't usually matter as it was quite subtle, and the shape of the real/virtual rooms typically matched up anyway."

Bluescreen preserve of PAL

Knightmare was successfully exported around Europe. Adaptations began in France and Spain, while German companies also showed significant interest.

But the colour encoding system for analogue television limited Knightmare to a European audience. PAL (Phase Alternating Line) used in Europe has a higher resolution than NTSC, with 576 visible lines compared to 486.

A 1992 pilot named 'Lords of the Game' was produced in Norwich for the US market. But American production companies at the time were unnerved by chromakey because of its technical complexity and the bluescreen issues they faced with NTSC.